Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

-

By using this site you agree to the terms, rules, and privacy policy.

-

@mosaic01 says: "I think dextrose will turn out to be the primary antidote to chronic copper overload. The lack of glycogen in the brain and liver is probably the actual cause of unusable copper accumulating in the first place..." -- Click Here to read rest of post

-

The Forum is transitioning to a subscription-based membership model - Click Here To Read

Click Here if you want to upgrade your account

If you were able to post but cannot do so now, send an email to admin at raypeatforum dot com and include your username and we will fix that right up for you.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Soluble Fiber Causes Liver Cancer, Insoluble And Antibiotics Prevent/stop It

- Thread starter haidut

- Start date

frannybananny

Member

- Joined

- Apr 26, 2018

- Messages

- 705

Perhaps one of the most controversial topics in Peat-land is fiber. Over the years he has consistently recommended insoluble fiber, such as found in carrots/mushrooms/bamboo, while recommending explicitly against soluble fiber such as pectin and other fermentable starches. I think in one of his interviews he said something along the lines of "For people with low metabolism or sensitive GI tract, intake of fermentable starches should be zero". In addition, he has explicitly cautioned against pectin and resistant starches found in whole grain bread, legumes, and some roots.

In contrast, the mainstream medical and nutrition industry recommends the exact opposite - i.e. eating 6-7 servings daily of resistant (fermentable) starches and supplementing with plenty of other fibers such as pectin whenever possible. Why? Because soluble fibers lower cholesterol. Well, the FDA already reversed its stance on cholesterol, but the ads for soluble fiber became even more intense after that. One of the most fashionable soluble fiber supplements on the blogosphere currently is fructooligosaccharides (FOS).

Fructooligosaccharide - Wikipedia

The study below drives a stake directly into the heart of that pseudo-medical claim of soluble fiber benefits. It found that despite the reduction in weight seen in animals fed soluble fiber, at least 40% of them developed liver cancer (HCC). Even worse, when the soluble fiber was combined with high-fat diet, the HCC incidence rose to 65% even in mice without gut dysbiosis. The study specifically tested inulin, pectin and FOS but states that the same mechanism is likely to manifest for any type of soluble fiber, including the widely used guar gum (even in organic products). The main experiment used a diet with 7.5% inulin but the study also tested diets with inulin content as low as 2.5% and found the same incidence of HCC. The soluble fiber was a causative "precursor" acting in synergy with gut bacteria. The bacteria digested the fiber and produced inflammatory metabolites, butyrate and bile acids. It was those metabolites and inflammation that caused the HCC. Butyrate fed on its own did not cause HCC but did fatten the liver when used in high amounts. However, unlike other studies, this one did NOT implicate endotoxin or its receptor (TLR4) as the sole cause because animals bred to be immune to endotoxin also developed cancer, albeit at lower rates. The study found that gut dysbiosis is required for HCC development, and specifically some bacterial species overpopulating the gut. The most prominent one was the Clostridia species. Soluble fiber administered to animals with sterile guts (as a result of antibiotics) or gut without dysbiosis did not result in HCC. This highlights once again the key role of gut health in almost any chronic disease - namely, undigested food or fiber feeds the bacteria in the colon and results in inflammation, fibrosis and eventually cancer. Endotoxin makes this process much more pathogenic but it is a not requirement for HCC to develop. More bad news - the animals with gut dysbiosis housed together with animals without resulted in the animals without dysbiosis also acquiring it, and developing HCC at the same rate if fed soluble fiber. So, this suggests that if we live among people with gut dysbiosis we tend to acquire it as well over time. In other words, the carcinogenicity potential is transmissible. I have seen evidence of this first-hand in the form of co-workers getting the same GI complaints after a few months of working along others with known GI issues.

Any good news? Yes, thankfully. Providing insoluble fiber in the diet (cellulose) or antibiotics, prevented the development of HCC. And if only insoluble fiber was fed in the diet, the animals did not develop HCC even though they ate the equivalent to "junk food" throughout the experiment. The antibiotics used to sterilize the gut were a simple combination of ampicillin and neomycin. More than 90% microbiota depletion was seen after 12 weeks on the antibiotic regimen, even though beneficial effects were seen even after only a week. The HED for those two antibiotics were about 14 mg/kg and 7 mg/kg respectively, and both have known good safety profiles. Another alternative that also worked was the antibiotic methronidazole, at the same dose as the ampicillin, but that antibiotic is a known carcinogen, so I think the former simple combination would much safer.

More good news? Drinking beer may also confer a protective effect against HCCMore of joke really, as it is specific acids present in treated hops that were protective due to preventing inulin fermentation by bacteria. Beer itself, being an alcoholic drink, may be not so good considering it increases endotoxin and is also estrogenic.

DEFINE_ME

"...Feeding T5KO mice ICD lowered incidence of obesity in 40% of mice, relative to what was observed for such mice fed a grainbased chow diet (Singh et al., 2015; Vijay-Kumar et al., 2010). The prevention of weight gain in this 40% subset of mice (Figure S1A) correlated with a reduction in indices of metabolic syndrome (Figures S1B–S1F). The hyperphagia of T5KO mice (Vijay-Kumar et al., 2010) was unabated, as their average food intake remained higher than WT mice (Figure S1G). However, while preparing serum samples, we observed that the 40% subset that seemingly lacked metabolic syndrome displayed a striking fluorescent yellow hue in their sera (Figure S1H), which begged investigation."

"...The reduced serum albumin in HB mice further implied impairment in liver function (Figure S1Q). To examine whether erythrocyte hemolysis contributed to H-bili, hematology was performed. Although HB mice exhibited leukocytosis, there were no differences in hematocrits between ICDfed HB, NB, and WT mice (Table S2). Lack of hemolytic anemia or defects in hepatic bilirubin conjugation suggested that the H-bili was likely due to a chronic liver disorder."

"...Gross analysis of liver following 6 months of ICD feeding revealed that 40% of T5KO mice and 0% of WT mice developed multinodular HCC (Figures 1A and 1B) with elevated serum a-fetoprotein (AFP) (Figure 1C). Tumors were primary and liver-specific, displaying a trabecular pattern, mitotic figures, anisocytosis, cell swelling, apoptotic bodies, ectopic lymphoid aggregates, and formation of atypical bile ducts (Figures 1D–1I) with the tumor demarcated by the substantial loss and distorted reticulin network (Figure 1I, iii). Increased expression of cytokeratin-19 (CK-19) was observed in certain regions of the tumor with atypical bile ducts, suggesting potential involvement of biliary cholangiocytes (Figure 1I, iv). In contrast, non-tumor regions exhibited inflammation, hepatic lipidosis, necrosis, and anisocytosis. No histological signs of tumorigenesis were observed in adjacent organs (lungs, pancreas, kidney, and colon; data not shown). HB mice were moribund and required euthanasia at 12–14 months of age (Video S1). Large tumor nodules spanning the entire liver were observed upon exitus (Figure 1J)"

"...Spontaneous inflammation in T5KO mice is driven, in part, by compensatory upregulation of other PRR, such as TLR4 and NLRC4 (Vijay-Kumar et al., 2007). Hence, we next investigated whether genetic deletion of Tlr4 in T5KO mice may attenuate ICD-induced HCC. This was not the case as penetrance (36%) and morphology of hepatic tumors in T5/Tlr4 double knockout (DKO) mice fed ICD was indistinguishable from the HCC observed in T5KO mice (data not shown). Nor did deletion of Tlrc4 confer any protection as ICD-fed T5/Nlrc4-DKO mice also displayed HCC (data not shown). Phenotypes associated with TLR5 deficiency are not specific to this receptor per se, but are more aligned to the chronic inflammation arising due to innate immune deficiencies. Hence, we next investigated if mice with other discrete innate immune deficiencies might develop HCC following ICD feeding. Tlr4KO mice also developed H-bili and HCC following 6 months of ICD feeding, albeit at a lower penetrance (17%, Figures S2H– S2K)."

"...To elucidate whether other types of soluble fiber can promote HCC, we replaced ICD’s inulin (long-chain b-(2 / 1) polyfructosan) with pectin (a-(1 / 4) poly-D-galacturonate) (Table S1, pectin-contain diet [PCD]). After 6 months of feeding, 2 out of 15 (13%) PCD-fed T5KO mice recapitulated the metabolic phenotype of HB mice, i.e., low body weight (data not shown), elevated serum bilirubin, ALT, and AFP and, moreover, developed multinodular HCC (Figures 2A–2F). Similar results were observed when the soluble fiber component was substituted with fructooligosaccharides (FOS) (short-chain b-(2 / 1) polyfructosan), wherein 2 out of 16 T5KO mice (12.5%) were positive for H-bili and HCC upon feeding of FOS-containing diet (FCD) for 6 months (Figures 2G–2L; Table S1). While such incidences of HCC in PCD and FCD fed mice were lower than the 40%–50% observed in ICD-fed T5KO mice, the former is nonetheless a relatively high incidence as this disorder is extremely rare in mice (Caviglia and Schwabe, 2015). Reducing the amount of soluble fiber in the diet by 70% (2.5% inulin w/w) was still sufficient to induce HCC (i.e., 4 out of 22 mice were positive for H-bili and HCC) (Figures 2M–2R). In contrast, T5KO mice fed a diet that lacked fermentable fiber and, rather, contained 10% cellulose (fermentation-resistant b-(1 / 4) D-glucose polymer, cellulose-containing diet [CCD]) did not develop HCC (Figures 2S–2V)."

"...Feeding HFD-I, but not HFD-cellulose, increased the incidence of HCC from 40% to 65% in T5KO mice (Figures S3I–S3N). These HCC-positive T5KO mice displayed attenuated indices of metabolic syndrome (data not shown), but elevated serum bilirubin, AFP, and ALT (Figures S3I–S3K). Unlike the modest HCC in WT HB mice, T5KO HB mice displayed multinodular HCC at the gross and histological level (Figures S3L–S3N). These findings suggest that metabolic perturbation has a role in the progression of HCC, and induction of HCC upon consumption of soluble fiber is applicable to WT mice, at least in the context of HFD."

"...Alteration in the make-up of microbial community due to diet was also observed between ICD- and CCD-fed T5KO mice (Figures 3F and 3G). Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) identified 753 bacterial taxa that were differentially altered between ICD-fed HB, NB, and WT mice. Taxonomy cladograms from LEfSe analyses revealed that Clostridia predominantly distinguished HB from the other groups (Figures 3H and 3I). Clostridia members (phylum Firmicutes) comprise a constellation of fiber-fermenting bacteria, particularly the Clostridium cluster XIVa, which are the main producers of butyrate and secondary bile acids (Van den Abbeele et al., 2013). In addition, the phylum Proteobacteria was also found to be strongly associated with H-bili. Overgrowth of Proteobacteria was noteworthy as it occurs in a spectrum of disease states and is implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis in humans (Gra˛ t et al., 2016). Furthermore, metagenome prediction analysis identified enrichment in genes encoding for fatty acid/lipid biosynthesis as well as motility/secretion (data not shown) in HB mice. These results correlated with the increased microbiota byproducts (i.e., LPS, flagellin) in the gut of HB mice and the markers of their systemic dissemination (Figures 3J–3N)."

"...Metabolic syndrome in T5KO mice is predominantly driven by the acquired gut dysbiosis, which is dependent on the microbes present in the facility in which the mice are raised (Letran et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2015). We hypothesized that perhaps ICD feeding may not induce HCC in T5KO mice reared in a manner that does not result in severe dysbiosis. Indeed, ‘‘non-dysbiotic’’ T5KO mice (Letran et al., 2011) procured directly from Jackson Laboratories failed to develop icteric HCC upon ICD feeding (data not shown), whereas mice bred independently in Pennsylvania State University, Georgia State University, and University of Toledo consistently displayed 35%–50% incidence of HCC upon ICD-feeding in repeated experiments. Liver-specific T5KO mice, having an intact intestinal TLR5 (Etienne-Mesmin et al., 2016), also did not develop icteric HCC upon ICD feeding (Figures S4D–S4G). To investigate the role of gut microbiota in ICD-induced HCC, we co-housed dysbiotic T5KO mice with WT mice, thus allowing the transfer of microbiota via coprophagy. Co-housing of WT and T5KO mice while maintained on ICD resulted in the development of HCC in both strains by 6 months (Figures 4A–4F). The development of HCC in cross-fostered WT mice (Figures 4G–4L) following ICD feeding further affirmed the role of microbiota in ICD-induced HCC. However, the cross-fostered T5KO mice were not protected from ICD-induced HCC (data not shown). Notably, microbiota ablation with broad-spectrum antibiotics mitigated HCC in ICD-fed T5KO mice (Figures S4H–S4K). Only 1 out of 12 antibiotic-treated T5KO mice exhibited a slight increase in serum bilirubin, AFP, ALT, but no tumors were evident. Moreover, germ-free T5KO mice fed irradiated ICD did not recapitulate either H-bili or HCC (Figures 4M–4P). Altogether, these findings indicate that a dysbiotic microbiota is required to develop HCC upon prolonged feeding with ICD and suggest that such oncogenic microbiota is transmissible to susceptible hosts."

"...To investigate the applicability of such findings in vivo, we administered butyrate (100 mM) in drinking water to T5KO mice for 9 months. A large subset of butyrate-treated mice (54%) displayed H-bili, hepatic inflammation, and upregulation of liver fibrosis and HCC markers, although no tumors were observed (Figures S4P–S4Z). Lack of tumorigenesis by butyrate alone suggests that ICD-induced HCC may require other metabolites/factors, possibly PRR ligands or bile acid dysmetabolism, although further studies are required to ascertain their contribution as a ‘‘second hit’’ to HCC pathogenesis."

"...Our hypothesis that fermentation of inulin promotes HCC holds that its inhibition may reduce HCC incidence. To test this notion, we depleted butyrate-producing bacteria by administering metronidazole (Kaiko et al., 2016; Louis and Flint, 2007) to ICD-fed T5KO mice. Metronidazole-treated T5KO mice displayed a reduced cecal butyrate (Figure 5A) and butyrate-producers (data not shown). Remarkably, the incidence of HCC was reduced in metronidazole-treated T5KO mice fed ICD for 6 months, albeit not eliminated (Figures 5B–5E)."

"...Next, we tested whether inhibiting bacterial fermentation by plant-derived b-acids from hops (Humulus lupulus) might reduce HCC in ICD-fed mice. b-acids are commercially used to preserve beer from spoilage (Sakamoto and Konings, 2003) and have been employed to inhibit hindgut fermentation of inulin in horses and cattle (Flythe and Aiken, 2010; Harlow et al., 2014). Treatment of ICD-fed T5KO mice with b-acids at 20 ppm dose lowered cecal butyrate (Figure 5F), without impacting gut bacterial loads (data not shown). Moreover, none of the T5KO mice that received 20 ppm b-acids along with ICD developed HCC. b-acids reduced incidence of HCC in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 5G–5J)."

"...Last, we examined whether HCC initiated by ICD could be halted by removing fermentable fiber from the diet. We identified pre-HCC mice at 2 weeks of ICD feeding by screening for serum bilirubin as a surrogate marker. These HB mice were either continued on ICD or immediately switched onto cellulose containing diet (CCD) for the remainder of the 6 months. While ICD-fed HB mice developed robust HCC, those that were switched to CCD were substantially protected and displayed marked decreases in serum bilirubin, ALT, and AFP (Figures 5K–5O). Together, these results argue strongly that prolonged exposure to microbial fermentation of soluble fiber drives HCC development in ICD-fed dysbiotic mice."

"...Next, we asked whether intervening with cholestyramine to specifically inhibit the enterohepatic recycling of bile acids could impact ICD-induced HCC. As anticipated, supplementing ICD with cholestyramine to HB mice substantially reduced their serum total bilirubin and ALT, but no change in AFP and TBA (Figures S6A–S6D). More importantly, these mice do not display visible tumors at the gross or histologic level. However, these outcomes do not rule out that the HCC may be delayed, rather than prevented, as the livers of these mice still displayed abnormal internal structure (Figure S6E). It is likely that cholestyramine could only prevent the reabsorption of bile acids and thus mitigated the disease, but inadequate to abate the cholestasis and injury induced by ICD."

"...Approximately one-half of United States adults consume dietary supplements (Bailey et al., 2011) that are purported to improve health. The general goal of such supplements is to provide purified versions of specific beneficial components of foods long associated with health, especially fruits and vegetables. However, some consumers of these products develop adverse effects, including jaundice and cholestasis following intake of multi-ingredient plant-derived supplements (Navarro et al., 2017). Accordingly, the United States Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) study (Navarro et al., 2014) states that plant-derived, and purified, supplements are not universally harmless. The current study extends this concept to highly refined fermentable fibers, which we show can promote cholestasis and subsequently HCC in mice. Such findings should give pause to the common and increasing incorporation of such fibers into processed foods that might contribute to the recently defined association of consumption of ultra-processed foods with incidence of cancer (Fiolet et al., 2018). Thus, further studies are urgently needed to determine whether processed soluble fibers promote cholestasis and HCC in humans."

"...Specifically, we reported that mice consuming purified, compositionally defined diets (CDD) that lack fermentable fiber display gut atrophy, which is corrected by enrichment of such diets with inulin (Chassaing et al., 2015b). The administration of inulin to mice also improves metabolic parameters and protects against obesity (Zou et al., 2018). However, further study has led us to appreciate that consumption of processed foods enriched with purified fibers may have dire consequences in certain contexts. For instance, we observed that mice consuming inulin-enriched CDD develop severe colitis upon exposure to the chemical colitogen DSS (Miles et al., 2017). We herein report that prolonged feeding of fermentable fiber-enriched CDD to mice with pre-existing microbiota dysbiosis such as, but by no means limited to, T5KO mice, resulted in development of cholestatic HCC. In contrast, there were no indications of liver disease in T5KO mice that consumed similar amounts of inulin added to grain-based rodent chow (data not shown), which is a relatively unrefined conglomerate of food scraps that has classically served as the standard diet for rodents used in research. These results suggest that the dietary context (i.e., refined or unrefined diet) in which a fermentable fiber is consumed is of great importance and, in particular, caution against enriching highly refined foods with fermentable fibers."

"...To date, gut microbiota have been strongly implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis as a result of sustaining hepatic inflammation via activating TLR4 (Dapito et al., 2012) or producing cytotoxic secondary bile acids (Yamada et al., 2018; Yoshimoto et al., 2013). In this study, we report the potential concerted role for microbiota dysbiosis, SCFA and bile acid dysmetabolism, and hepatic inflammation in promoting HCC. The dysbiosis in HCC-developing mice fed ICD was marked by several key ‘‘signatures’’: (1) increase in total bacterial load, (2) loss in species richness and diversity, (3) increase in Proteobacteria, (4) distinct enrichment of Clostridia spp. and other fiber-fermenting bacteria, and (5) atypical elevation of secondary bile acids in the systemic circulation. Enrichment of Proteobacteria is evident even before any dietary interventions in the T5KO mice, which eventually developed ICD-induced HCC. Keeping Proteobacteria species, a number of which are considered opportunistic pathogens, in-check is an important function of innate immunity in the gut. The failure to do so may explain why not only T5KO mice, but also Tlr4KO and Lcn2KO mice were prone to ICD-induced HCC."

"...We fully appreciate that a number of studies have observed the anti-tumorigenic effect of inulin and SCFA (Pool-Zobel, 2005). However, we speculate that generation of large amounts of butyrate in a context of dysbiosis, cholemia, and inflammation may instead create a tumor-promoting microenvironment that outweighs any of its beneficial effects. This consideration is in accord with the ‘‘butyrate paradox,’’ which argues that the ability of this SCFA to promote or impede cell proliferation is contextually dependent on the cell-type, time, and the amount of exposure (Donohoe et al., 2012). The doses of SCFA exceeding the threshold tolerable by the host have been shown to aggravate colonic inflammation (Kaiko et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2013) and tumorigenesis (Belcheva et al., 2014; Misikangas et al., 2008; Pajari et al., 2003), induce urethritis and hydronephrosis (Park et al., 2016), and promote obesity by aggravating hepatic lipogenesis (Singh et al., 2015) and hyperphagia (Perry et al., 2016). Janssen et al. (2017) reported that feeding of guar gum (a soluble fiber comprised of mannose [b 1,4-linked] and galactose [1,6-linked]) for 18 weeks protected mice from diet-induced obesity but eventuated hepatic inflammation and fibrosis associated with increased plasma TBA and disrupted enterohepatic circulation). Although Janssen et al. (2017) did not observe HCC, their observations nonetheless reiterate that the intake of soluble fiber may not be beneficial to the liver in the absence of a functional gut microbiota."

"...In summary, our study documents the unexpected observation that prolonged consumption of fermentable fiber enriched foods by mice prone to dysbiosis results in HCC. Such HCC, first observed in, but not limited to, T5KO mice, is reminiscent of human icteric HCC encompassing key features of progressive cholestasis, steatohepatitis, and tumorigenesis (Arteel, 2013). The most intriguing and key finding of this study is the absolute requirement of soluble fiber-feeding to develop HCC. We demonstrated that interventions that deplete butyrate-producing bacteria, inhibit gut fermentation, exclude soluble fiber from the diet, or prevent enterohepatic recycling of bile acids, are feasible strategies to mitigate such ICD-induced HCC. The identification of oncogenic bacteria, however, remains elusive and is complicated by the extent to which gut bacteria participate in inter-species cross-feeding of SCFA (Wrzosek et al., 2013). Yet, it is intriguing to note that our observations on the adverse effects of

fermentable fiber is not restricted to inulin alone, but broadly applicable to other types of soluble fibers, including pectin and FOS."

Please what does ICD stand for?

frannybananny

Member

- Joined

- Apr 26, 2018

- Messages

- 705

I see wheat bran but what about wheat germ? ....a good source of betaine.The ones with mostly insoluble fiber include carrots, turnips, mushrooms, bamboo shoots, wheat bran, raspberries, strawberries, and some pears. Most starchy foods contain enough soluble fiber to cause digestive issue separately from the GI inflammation the starch itself can cause.

Inulin-Containing DietPlease what does ICD stand for?

Not all dietary fiber is created equal: cereal fiber but not fruit or vegetable fibers are linked with lower inflammation

Researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and colleagues evaluated whether dietary fiber intake was associated with a decrease in inflammation in older adults and if fiber was inversely related to cardiovascular disease. The results showed that total fiber, and more specifically cereal fiber but not fruit or vegetable fiber, was consistently associated with lower inflammation and lower CVD incidence. Until now there had been limited data on the link between fiber and inflammation among older adults, who have higher levels of inflammation compared with younger adults. The study findings are published in JAMA Network Open.Not all dietary fiber is created equal: cereal fiber but not fruit or vegetable fibers are linked with lower inflammation

Researchers evaluated whether dietary fiber intake was associated with a decrease in inflammation in older adults and if fiber was inversely related to cardiovascular disease. The results showed that total fiber, and more specifically cereal fiber but not fruit or vegetable fiber, was...

www.sciencedaily.com

frannybananny

Member

- Joined

- Apr 26, 2018

- Messages

- 705

Thank you!Inulin-Containing Diet

Beneficial and detrimental effects of processed dietary fibers on intestinal and liver health: health benefits of refined dietary fibers need to be redefined!

Consumption of processed foods—which are generally composed of nutritionally starved refined ingredients—has increased exponentially worldwide. A rise in public health awareness that low fiber intake is strongly linked to new-age disorders ...

Structurally distinct dietary fibers differentially modulate intestinal health

FDFs (refined dietary fibers) are well tolerated by healthy individuals and consuming an adequate amount of FDFs can provide numerous health benefits. Contrarily, a subset of IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) patients experience poor tolerance to certain types of fiber, including inulin-type fructans commonly present in the FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols). In our recent study, we showed that two structurally distinct FDFs (inulin and pectin) behave oppositely in the inflamed gut (Figure. 1), which emphasizes the complexity of fiber intolerance in IBD patients. To understand the fundamental mechanisms of why inulin aggravated intestinal inflammation, we analysed both the composition and the metabolic products of the GM (gut microbiota) in cecal contents, which revealed that inulin specifically promoted the expansion of γ-Proteobacteria, a well-known opportunistic pathogen, and an abundance of butyrate when compared to mice fed pectin and cellulose as a DF (dietary fiber) source. Further, oral feeding of tributyrin, the triglyceride form of butyrate, exacerbating colonic inflammation affirmed that elevated butyrate could be detrimental during heightened colonic inflammation triggered via loss of IL-10 function. Exacerbated colitis in the inulin-fed group was also associated with augmented IL-1β activity, where inhibition of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) by genetic, pharmacologic, or dietary means diminished colitis. Collectively, our study partly explains why limiting or avoiding foods that contain high FDFs—or consuming a low-FODMAP diet—improves clinical complications in IBD patients. Remarkably, pectin used in this study improved colonic inflammation. Collectively, accumulated data suggest that not all DFs are created equally or ferment uniformly, and do not provide similar effects on host gastrointestinal health.Figure 1. Dietary fiber pectin, but not inulin, protects against colonic inflammation. The image depicts the distinct effect of fermentable dietary fiber on colonic inflammation induced via loss of IL-10 signaling. All changes are relative to control-diet (cellulose)-fed mice.

Beneficial and detrimental effects of processed dietary fibers on intestinal and liver health: health benefits of refined dietary fibers need to be redefined!

Consumption of processed foods—which are generally composed of nutritionally starved refined ingredients—has increased exponentially worldwide. A rise in public health awareness that low fiber intake is strongly linked to new-age disorders ...www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Structurally distinct dietary fibers differentially modulate intestinal health

FDFs (refined dietary fibers) are well tolerated by healthy individuals and consuming an adequate amount of FDFs can provide numerous health benefits. Contrarily, a subset of IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) patients experience poor tolerance to certain types of fiber, including inulin-type fructans commonly present in the FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols). In our recent study, we showed that two structurally distinct FDFs (inulin and pectin) behave oppositely in the inflamed gut (Figure. 1), which emphasizes the complexity of fiber intolerance in IBD patients. To understand the fundamental mechanisms of why inulin aggravated intestinal inflammation, we analysed both the composition and the metabolic products of the GM (gut microbiota) in cecal contents, which revealed that inulin specifically promoted the expansion of γ-Proteobacteria, a well-known opportunistic pathogen, and an abundance of butyrate when compared to mice fed pectin and cellulose as a DF (dietary fiber) source. Further, oral feeding of tributyrin, the triglyceride form of butyrate, exacerbating colonic inflammation affirmed that elevated butyrate could be detrimental during heightened colonic inflammation triggered via loss of IL-10 function. Exacerbated colitis in the inulin-fed group was also associated with augmented IL-1β activity, where inhibition of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) by genetic, pharmacologic, or dietary means diminished colitis. Collectively, our study partly explains why limiting or avoiding foods that contain high FDFs—or consuming a low-FODMAP diet—improves clinical complications in IBD patients. Remarkably, pectin used in this study improved colonic inflammation. Collectively, accumulated data suggest that not all DFs are created equally or ferment uniformly, and do not provide similar effects on host gastrointestinal health.

View attachment 36032

Figure 1. Dietary fiber pectin, but not inulin, protects against colonic inflammation. The image depicts the distinct effect of fermentable dietary fiber on colonic inflammation induced via loss of IL-10 signaling. All changes are relative to control-diet (cellulose)-fed mice.

Explains why jam helps me poo

contains pectin...

i have painful IBS-C, and from experience, beta glucans and less so psyllium were major triggers, not pectin regardless of insoluble fiber content.In addition, he has explicitly cautioned against pectin and resistant starches found in whole grain bread, legumes, and some roots.

carrots are pectin foods, fine either cooked or raw. oranges too.

oatmeals were a very bad experience, almost killed me (after a week or so, not the first day). it did improve transit but it worsen pain, after some days.

i think beta glucans are causing bad reaction in weat, not other soluble fibers.

buckwheat it's so great, I've been using long term with no side effects and usually improved my IBS-C pain. the only mild side effect is fast transit, cause my main problem is pain, I'm usually not that constipated whatever i eat.

buckwheat it's high in soluble fiber but without beta glucans i think, and it's low fodmap.

mushrooms contain beta glucans and tend to cause me some symptoms too.

eating nutritional yeast was always a major triggers similar to oatmeal, they contain beta glucans in high quantity.

even coffee has soluble fiber. many peat foods do, especially pectin.

pectin and inulin may not be the culpit, maybe we should blame other soluble fibers instead, beta glucans for those with candida and maybe fodmaps in high amount.

i have painful IBS-C, and from experience, beta glucans and less so psyllium were major triggers, not pectin regardless of insoluble fiber content.

carrots are pectin foods, fine either cooked or raw. oranges too.

oatmeals were a very bad experience, almost killed me (after a week or so, not the first day). it did improve transit but it worsen pain, after some days.

i think beta glucans are causing bad reaction in weat, not other soluble fibers.

buckwheat it's so great, I've been using long term with no side effects and usually improved my IBS-C pain. the only mild side effect is fast transit, cause my main problem is pain, I'm usually not that constipated whatever i eat.

buckwheat it's high in soluble fiber but without beta glucans i think, and it's low fodmap.

mushrooms contain beta glucans and tend to cause me some symptoms too.

eating nutritional yeast was always a major triggers similar to oatmeal, they contain beta glucans in high quantity.

even coffee has soluble fiber. many peat foods do, especially pectin.

pectin and inulin may not be the culpit, maybe we should blame other soluble fibers instead, beta glucans for those with candida and maybe fodmaps in high amount.

How do you do with rice? I think all grains contain beta glucans, maybe that's why you do well with buckwheat, bc it isn't an actual grain.

Apart from mushrooms, if I'm not mistaken broccoli and sweet potatoes are high in beta glucans as well.

i do eat rice, mostly white. as long as i eat with some fiber like carrots, it's fine.How do you do with rice? I think all grains contain beta glucans, maybe that's why you do well with buckwheat, bc it isn't an actual grain.

Apart from mushrooms, if I'm not mistaken broccoli and sweet potatoes are high in beta glucans as well.

i don't eat sweet potatoes, broccoli almost never.

i like potatoes, white rice, winter squash sometimes, quinoa sometimes

oatmeal gave me rope worms after 2 weeks of eating them. i used to do enemas but never got those false worms. oatmeals were fine the first few days but then i got severe pain, after 2 weeks a started enemas and had those worms. i never had them after of before that, so I'm sure they are not made of mucus but they are made of beta glucans and psyllium like mucilage. very bad stuff for the gut.

Last edited:

Sorry, but it's important for those who want to know, the first image is the rope worm, actually it's very long but the photo did not show how long it is cause it's in the box.

the next photo is the next day after i let it sit with some water, the worm was hydrated and it transformed in a very sticky substance.

it's clearly beta glucans from oatmeal, especially i was eating almost nothing but oatmeals and milk the days prior to that.

the next photo is the next day after i let it sit with some water, the worm was hydrated and it transformed in a very sticky substance.

it's clearly beta glucans from oatmeal, especially i was eating almost nothing but oatmeals and milk the days prior to that.

Xemnoraq

Member

- Joined

- Oct 3, 2016

- Messages

- 271

- Age

- 28

Does this include fruit pectin such as whats added in jam?

good question. seems it's unavoidable since practically all commercial jams/preserves contain it. also seems it's usually a relatively small proportion per serving so it can probably be disregarded.Does this include fruit pectin such as whats added in jam?

Last edited:

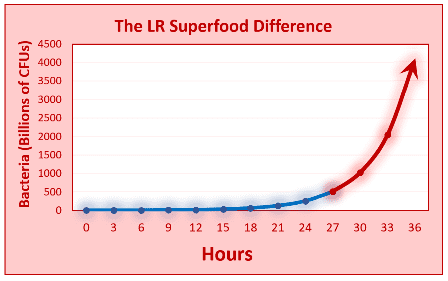

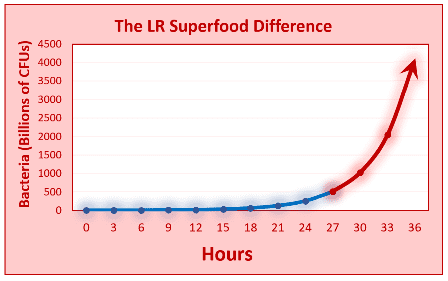

I cannot tell from the study, but, would inulin be bad if used to make homemade yogurt (L. reuteri, which is said by Peat to be a mild antibiotic)?

The inulin is used to feed the L. reuteri, which grows for 36 hours on the counter in a Luvele yogurt maker.

(I then strain the yogurt to get rid of the whey and lactic acid)

The point being that most of the inulin is consumed as an energy source by L. reuteri during those 36 hours.

I then consume 8 oz of the yogurt each day.

The inulin is used to feed the L. reuteri, which grows for 36 hours on the counter in a Luvele yogurt maker.

(I then strain the yogurt to get rid of the whey and lactic acid)

The point being that most of the inulin is consumed as an energy source by L. reuteri during those 36 hours.

I then consume 8 oz of the yogurt each day.

not sure but doesn't it already have enough to feed on? having made yogurt on the kitchen counter (then fridge), didn't need to feed/add anything else to the milk and starter yogurt mixture.I cannot tell from the study, but, would inulin be bad if used to make homemade yogurt (L. reuteri, which is said by Peat to be a mild antibiotic)?

The inulin is used to feed the L. reuteri, which grows for 36 hours on the counter in a Luvele yogurt maker.

(I then strain the yogurt to get rid of the whey and lactic acid)

The point being that most of the inulin is consumed as an energy source by L. reuteri during those 36 hours.

I then consume 8 oz of the yogurt each day.

for ages, yogurt was made, even commercially, without having to to contain inulin (or gelatin (not so bad), or pectin, or gums, etc.)

seems the inulin etc are nowadays often added to commercial yogurts more for homogenizing/looks reasons for producers' convenience and to appeal to consumers who don't realize that it's normal for yogurt to separate (into liquid and solid) and it doesn't mean that it's gone bad (ie yogurt is different from ice cream or pudding.) all one has to do is stir the liquid and solid back together. or if he prefers, drain the liquid, as you so wisely

David PS

Member

Your fermented L. reuteri milk product is not yogurt. It does not meet the FDA's formal definition of yogurt and could not be sold commerically as a yogurt even though it looks and smells like yogurt. seeI cannot tell from the study, but, would inulin be bad if used to make homemade yogurt (L. reuteri, which is said by Peat to be a mild antibiotic)?

The inulin is used to feed the L. reuteri, which grows for 36 hours on the counter in a Luvele yogurt maker.

(I then strain the yogurt to get rid of the whey and lactic acid)

The point being that most of the inulin is consumed as an energy source by L. reuteri during those 36 hours.

I then consume 8 oz of the yogurt each day.

CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21

www.accessdata.fda.gov

Your correct that the inulin is added as a feed so that the L. reuteri (shown as LR in chart below) can continue to multiply for 36 hours. It is the length of time that the LR ferments that makes the fermented L. reuteri milk product thick.

Last edited:

David PS

Member

Mixing the whey and lactic acid back into the fermented milk product (whether it is yogurt or not) is not recommended by Dr. Peat. He recommends straining the yogurt and discarding the whey (containing lactate). See his 2 newsletters about lactate.not sure but doesn't it already have enough to feed on? having made yogurt on the kitchen counter (then fridge), didn't need to feed/add anything else to the milk and starter yogurt mixture.

for ages, yogurt was made, even commercially, without having to to contain inulin (or gelatin (not so bad), or pectin, or gums, etc.)

seems the inulin etc are nowadays often added to commercial yogurts more for homogenizing/looks reasons for producers' convenience and to appeal to consumers who don't realize that it's normal for yogurt to separate (into liquid and solid) and it doesn't mean that it's gone bad (ie yogurt is different from ice cream or pudding.) all one has to do is stir the liquid and solid back together. or if he prefers, drain the liquid, as you so wiselydo.

2009 Lactate vs. CO2 in wounds, sickness, and aging; the other approach to cancer (Ray Peat)

2020 09 Lactate, metabolic regression, & political-medical implications (Ray Peat) [PDF]

A friend suggested coconut flour instead of inulin.Your fermented L. reuteri milk product is not yogurt. It does not meet the FDA's formal definition of yogurt and could not be sold commerically as a yogurt even though it looks and smells like yogurt. see

CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21

www.accessdata.fda.gov

Your correct that the inulin is added as a feed so that the L. reuteri (shown as LR in chart below) can continue to multiply for 36 hours. It is the length of time that the LR ferments that makes the fermented L. reuteri milk product thick.

Coconut flour is mostly insoluble fiber, and can apparently be used in this yogurt recipe in place of inulin.

So, I may try that.

Paul

That’s what I was referring to when i said wiselyMixing the whey and lactic acid back into the fermented milk product (whether it is yogurt or not) is not recommended by Dr. Peat. He recommends straining the yogurt and discarding the whey (containing lactate). See his 2 newsletters about lactate.

2009 Lactate vs. CO2 in wounds, sickness, and aging; the other approach to cancer (Ray Peat)

2020 09 Lactate, metabolic regression, & political-medical implications (Ray Peat) [PDF]

EMF Mitigation - Flush Niacin - Big 5 Minerals

Similar threads

- Replies

- 147

- Views

- 33K

- Replies

- 40

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 5K

- Replies

- 15

- Views

- 9K

- Replies

- 263

- Views

- 64K

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 5K

- Replies

- 20

- Views

- 10K

- Replies

- 17

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 95

- Views

- 17K

- Replies

- 602

- Views

- 216K